hpr2757 :: How to DM

Klaatu explains how to DM an RPG, and Lostnbronx demonstrates, step by step, how to build a dungeon

Hosted by Klaatu on Tuesday, 2019-02-26 is flagged as Clean and is released under a CC-BY-SA license.

rpg, dm, gm, game master, dungeon master, dnd.

(Be the first).

Listen in ogg,

opus,

or mp3 format. Play now:

Duration: 00:44:54

Download the transcription and

subtitles.

Tabletop Gaming.

In this series, initiated by klaatu, analog games of various sorts are described and reviewed. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tabletop_game for details.

Klaatu

I've gotten a lot of great feedback on the Interface Zero play-through and the episode about getting started with RPGs I did with Lostnbronx. People have told me that one of the biggest blockers to getting started is knowing what to do as GM.

Now, I've read lots of rulebooks and GM guides, and it seems to me that most of them assume you've either played an RPG before, and so you've seen an example of a Game Master at play, or you've seen one on Youtube or Twitch. It's a safe assumption, but it's easy to forget all of those great examples under pressure. So in this episode, Lostnbronx and I are going to provide you with some clear and direct instructions on what exactly a GM does.

The short version is this:

Tell the players where they are and what they see around them.

Listen to the players when they tell you what they want to do.

Tell the players the outcome, based on your privileged knowledge of the game world or on a roll of the dice, of their actions.

You loop over that sequence, and you're game mastering!

But that makes for a short episode, and anyway, there are details about the process that we can talk about to make you feel more comfortable with the prospect of deciphering a game world with your friends.

To that end, Lostnbronx and I have started a website dedicated to gaming! You should check it out, subscribe to our feed. We discuss everything game-related there, plus a little tech and all manner of topics of interest to geeks.

Lostnbronx

Right off the bat, it's important to understand that every GM is different. No two styles of running a game match completely, nor should they. And while there's no one correct way to run a game, there are plenty of ways to do it poorly. The GM wears many hats, but in my opinion, the most important job is to make sure that everyone has a good time. Your players are giving you an evening out of their lives. Next week they'll probably give you another. It's your job to make sure that time isn't wasted.

By definition, games, even role-playing games, are a form of entertainment -- like reading a book, watching a movie, or enjoying the circus. When you go to that, the GM is the ringmaster, presenting the show; while the players are both the audience, and the main attraction. The GM controls the world, the people, the monsters, the history, even the weather. The GM controls everything, in fact...except for the player characters. A game master presents the situation, but it's the players who decide what to do with that information.

Now, this is all pretty vague, and describing RPG's is far less informative than playing them. Considering this is a podcast, I encourage you to go back and listen to Klaatu's aforementioned "Interface Zero" episodes. These are excellent examples of actual game play. If you're having a hard time imagining how RPG's are presented and experienced, you'll appreciate those shows.

Now then, almost all games are divided into genre types: sword and sorcery; space opera; spies; super-heroes; and pretty much everything else. And I mean everything! If there's a genre of fiction and storytelling that you enjoy, chances are there's a game or game setting for it somewhere. The most popular style of RPG's out there are fantasy. Think "Lord of the Rings". Think "Harry Potter". Think of anything, in fact, because all of it is possible.

A staple of the high fantasy genre of gaming is the dungeon. Now, that term has two meanings in this sort of game: first, the usual meaning, of what amounts to the basement of a castle, with jails, interrogation rooms, storage rooms, and more. The other meaning refers specifically to a type of adventuring environment. Both of these are usually found underground, but an adventuring dungeon may have nothing to do with any castle. It might be a lost crypt, a cave system, an abandoned gold mine, or the lair of some dreaded beast that's been terrorizing the countryside. In the dungeon might be enemies, monsters, and treasure protected by deadly traps. Magic abounds. There might be puzzles, dark secrets, or a kidnapped prince to rescue.

As a new GM, you can start off any way you want, but in my experience, the best way to get used to how the game works, and how the whole process of providing an evening's entertainment to your friends or family works in this context, is to create a dungeon and run your players through it.

Dungeons generally require set-up time; that is to say, you have to design it in advance. Now, Klaatu and I are currently working on ways to ease that burden, with the ultimate goal of eliminating the pre-work entirely. But for now, let's talk about the traditional way to approach all this. What follows is a step-by-step process, but understand, it's only one of an infinite possible number of them.

STEP 01 -- CREATE THE COUNTRYSIDE Some GM's say creating the world is the first step. Some say creating the godly pantheons of the world is the first. Some say it's the history, or the fantasy races. They're not wrong, but trust me, when you're just starting out, none of that stuff matters. In this example, you'll be running the players through a dungeon. That dungeon is out in the country, within the middle of a large forest.

Now, it will make the beginning and end of the adventure easier if you have a small village nearby where the player characters all live. We'll call it Forestdale for the lack of anything better. In Forestdale, there's an inn or tavern. This is where people get together, tell tall tales, and become inspired to go adventuring, so let's give it a name as well: "The Prancing Unicorn". That's home base. Every player character knows this place, and everyone in it knows them.

One of the stories being swapped at "The Unicorn" lately is about a tribe of dangerous creatures living in an underground lair somewhere within the forest. They are led by an evil wizard, or so the tales go. They have been attacking farmers and merchants who travel through the roads and foot paths of the woods in order to sell their goods in Forestdale. One of the merchants says he saw them travel down the Western path near the Old Bridge. Something must be done, but who would be brave or foolhardy enough to even try?

And that's all you need to create for the world right now. Remember, this stuff is new; no one needs large amounts of detail just yet, least of all you. You'll have enough to juggle.

STEP 02 -- CREATE THE DUNGEON FLOOR PLAN One of the rumors to be heard at "The Prancing Unicorn" is that there's an underground cave system or labyrinth somewhere in the forest. Some say it's a myth, others say their cousin's uncle's sister's best friend came across it once. Either way, its existence is shrouded in mystery, and people are said to go in, but not always come out.

This is your first dungeon. You don't want to do more work than you need to. Let's make this dungeon a single level. Later, you can add a secret panel somewhere that can reveal a set of stairs down to a second level (and from there, a third, fourth, tenth, or more). Right now, it's one level, hidden below the forest. It's dark, it's dangerous. It's plenty.

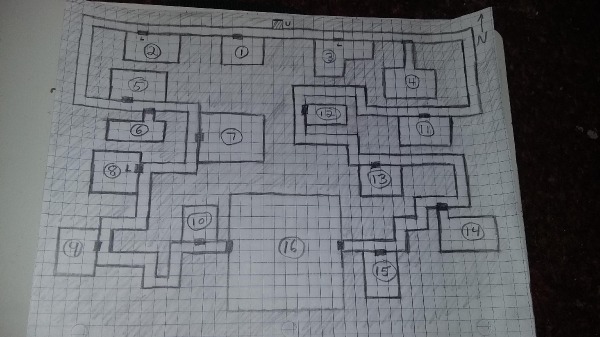

Putting a dungeon together can be difficult, but it doesn't have to be. The traditional way to create one of these is to use graph or hex paper and draw out the floor map. Each square of the graph paper is equal to ten feet, or, say, three meters. You make note of all rooms, caves, doors, hallways, stairs up or down, floor traps, hidden doors, and anything else you want in there. Be sure to put a set of stone stairs that lead from the forest above, down to this dank and gloomy dungeon.

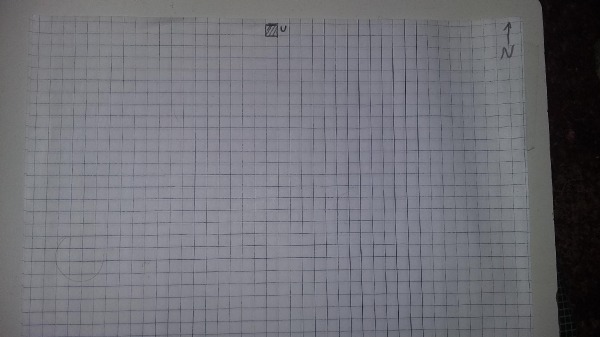

There are no standard symbols for the different things on the map, despite what anyone might tell you, but for now, let's turn the paper landscape style, and at the top of the page, now held that way, outline one square of the graph paper with a pencil. Inside the square, draw three or four small lines at an angle. This will represent a set of stairs. Next to the stairs, write the letter "U". This is the way to get to the forest above. Granted, it's how the player characters will come down here to begin with, but once they are here, they have to go up to leave, hence the "U". If that's confusing, you can write, "To The Forest Above", next to this square, maybe with a little arrow. You can write anything you want, but this is how the player characters will get in and out of your dungeon.

We're going to draw the floor plan from the top of the page down. The entire dungeon map will be on this one side of the paper. In the corner, draw an arrow pointing up, and put a letter "N" there. That's North. We'll be using compass directions from now on. Granted that when underground, it's hard to get your bearings without a compass, but for this first dungeon, we won't worry about that. North, South, East, West. It makes life easy.

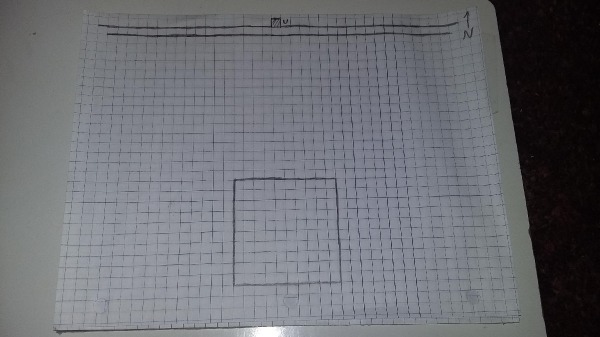

On the bottom of the page, to the South, draw a box in the middle of the page that's ten by ten squares in size. This is where the dungeon tunnels all will be leading, and where we'll have the biggest fight of the adventure. We're setting that up now, so we always know where we're heading. Now go back to the stairs at the top of the page.

Draw a long line from the lower edge of the stairs going West. Stop the line a square or two from the edge of the paper. Now do the same thing going East. Next, move down one square, and draw another line parallel to both of these, going entirely from one side of the page to the other, East to West. You've just created a place for the players to explore, so imagine it for a moment: they come down some broken, forgotten stairs. Let's say they travel at least a hundred feet down, tripping over tree roots and walking through cobwebs, until the stairs deposit them in the middle of a dark tunnel, ten feet wide. It stretches to either side, running East and West out of sight (you know that it goes hundreds of feet in both directions, but you'll let them discover that for themselves). They listen, and can hear nothing but the scurrying of unseen vermin. At least, they hope that's what it is. Not a bad start.

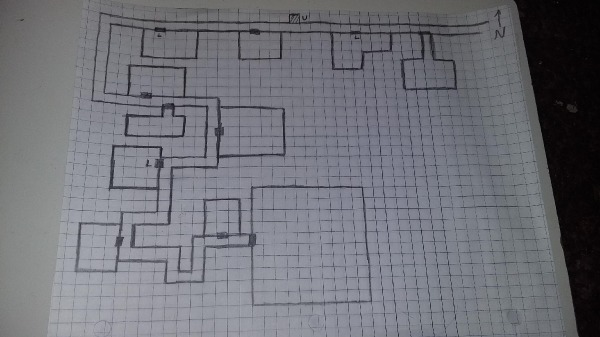

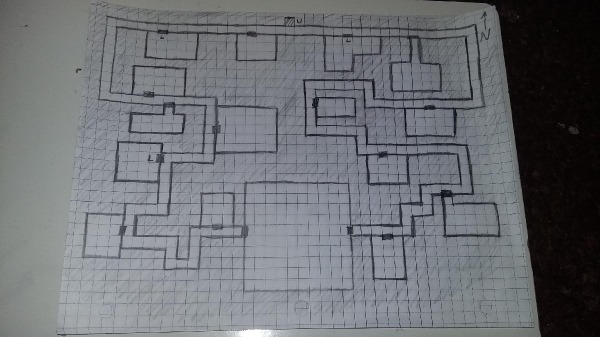

Along this hallway, you'll draw little rectangles, like black bars, on random squares along the Southern side of the tunnel. Not too many, just a few here and there, with generous space in between. These are heavy wooden doors. Some may be locked. That's your choice. If they are, put a little symbol near them. It could be as simple as the letter "L", so let's go with that. Now you know where the all doors are in this particular tunnel, and you know which of them will be a challenge for the player characters to open.

This is just the first tunnel of a larger complex. This complex can be as big or as small as you'd like. Let's say it's moderately sized. Before we draw more tunnels, let's draw the rooms behind those doors. This will tell us how much map space we'll have for further tunnels. Some GM's like to draw all the tunnels first, and then fit in the rooms. You can do it however way you want later on; right now, let's just use this method. Pick a door. Draw a box behind it, three or four squares in size. That's the room. Do the same behind the other doors. Make the rooms different shapes and sizes, but not too big. Let the big room at the bottom be the star. When you're done, you have a huge tunnel, with several mysterious doors, behind which are some good-sized rooms.

On the part of the tunnel that ends on the West side, draw a connecting tunnel South for five squares, and then turn the direction back to the East. Draw this tunnel going that way for ten squares. Put a door or two along here, and draw some rooms for them. Turn the tunnel South again, and go five or six squares, and turn it East again for four squares. Draw a door and room. Maybe it's locked, maybe not. Continue with this meandering, jagged floor plan, wandering East and then West, but always moving South. Add occasional doors and rooms as you go, until your tunnel finally ends on the Western side of the large ten by ten square room at the bottom of the page. Draw a door to get in there.

Now go back up to the long tunnel at the top, and repeat this whole process on the Eastern side, eventually bringing that part of the tunnel to the Eastern edge of the big room at the bottom. Put a door there.

Now, number your rooms on the map, starting at at the top, and working your way down, until you've marked each one. Room numbers are essential, because you'll be keeping track of each one.

The floor plan to your first dungeon is complete. Now you need to put interesting things in it.

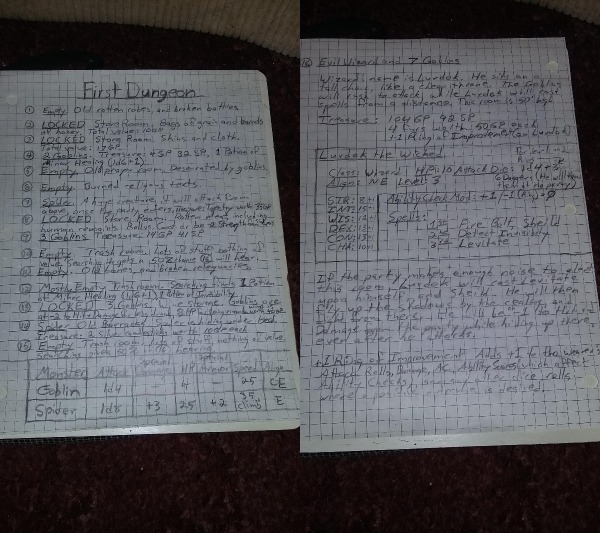

STEP 03 -- POPULATE YOUR DUNGEON Okay, on a separate piece of paper, list the rooms of your dungeon. Start at #1, and go down. Beside the room number, you put in a brief description, along with any monsters, treasure, or other points of interest. You'll be consulting this list throughout the game, so write down everything you need to know, in order to minimize the amount of time you'll inevitably have your nose in the rulebook while playing. Monster statistics, including their weapons, and and the damage they do, should all be on this list, though there are ways to simplify the process, once of which I'll go into in a moment.

When putting creatures and things into your dungeon, the first thing to remember is to not overload it. Each room does not need a monster. Not every room needs treasure. It might be helpful to think in terms of what you'd like to see in the dungeon as a whole. Remember the stories of evil creatures, and possibly a wizard, which you heard at "The Dancing Unicorn"? We'll use that as our springboard. This is a starting dungeon, not just for you, but also for the player characters. Starting dungeons mean low-level monsters, so let's go with goblins.

Goblins are generally quite impressed with magic, so we're going to assume a wizard of dubious character has bullied a small tribe of them into being his thugs. They've been waylaying passing merchants and farmers, stealing their wares, and carrying off food (along with the occasional peasant worker, as goblins love the taste of human flesh). Stupid, but dreadful creatures, they have displayed a level of tactical organization that's not normal for them. This, of course, is because the wizard's in charge. Look up the statistics for goblins, and understand what they're like. For this adventure, we're not going to worry about goblin captains, or goblin chiefs, both of which are tougher than your average goblin. No, all the creatures for this adventure have the same statistics. Don't drive yourself crazy writing them down, over and over. Write them once at the bottom of the room description page, and every time the player characters run into a goblin, consult them.

Let's say there are a total of fifteen goblins in this dungeon. They won't all be together; the player characters will encounter a few of them here and there, in various rooms, or maybe ust wandering the tunnels. The rooms themselves will have the spoils of all their raids, including barrels of wine, hams and sides of beef; furs, and a few copper, silver, and gold coins. If there's wine in one of the rooms, maybe the goblins there are drunk, fighting at a penalty to hit and damage. And remember, not all rooms need things in them. Maybe this was once a temple, and there's just broken furniture, and rotting religious robes in some of the rooms. In one, there might also be a tapestry against the wall, depicting a miracle of whatever god this place was once dedicated to. What you might not tell the player characters up front is that the tapestry could fetch a fair amount of gold coins in the market back in Forestdale. Too big to carry while exploring the dungeon, such a thing could always be rolled up and fetched on their way out. Not all treasure is found in wooden chests.

Then again, a lot of it is, so why not put one in the big room to the South? Of course, you have to defeat the evil wizard and his goblin cohorts, wh are hanging out in there. As a rule of thumb, you might want to sprinkle half the goblins throughout the dungeon, leaving the other half here, for the final fight. Stealth matters. Approaching the big room noisily, and kicking open one of the doors, is not stealthy. The player characters might be able to catch the wizard and his minions off-guard, if they move quietly.

In order to be a credible threat to the player characters, this wizard should be of a slightly higher level, say 2nd or 3rd. He'll have some aggressive spells, and he'll have his goblins handy. You'll roll up the wizard the same way the players rolled up their characters, only you'll make him more experienced, and with more spells at his command. Maybe he even has a magic item of some sort. Should the players defeat this guy, this magic item will be part of the treasure; until then, it's something the wizard will use against them. Don't make it too tough. Maybe don't make it tough at all: a +1 Ring of Protection, maybe. Or perhaps, a +1 dagger. That might not sound like much, but it's more than the player character's have when they start.

Not enough excitement, maybe? Just add in a couple of giant rats in one of the rooms. Maybe some large spiders in another. Don't forget to put their statistics down in the room description. Judging how tough or easy a dungeon needs to be comes with experience. My suggestion is to err on the side of toughness, to put more challenges in there than maybe you feel comfortable with. If the player characters are looking depleted and injured, you can say the room is empty, instead of filled with spiders. Also, it doesn't hurt at all to remind the players now and then that it's okay to retreat. They can always come back another day when they're rested, and have made plans based on the knowledge they gained the first time around. It sets up a grudge match...the heroes vs. the evil wizard and his goblin hoard. You, as the GM, just repopulate the goblins, move them around a bit, so they're not all in the same rooms as before (though the big room should still be for the final fight), and //voila//! You've just provided your players with two night's worth of entertainment, for the effort of only one.

And there you have it: a stocked dungeon that dovetails into the local lore of the countryside, ready for your players to explore.

STEP 04 -- ROLLING UP CHARACTERS Some GM's will want a whole night just for this process. Others will just have the players arrive at the game with their characters ready to go, especially if they are experienced with the game. I won't go over the character creation process here, because each game is different, and some are VERY different. I mention this now, though, because the players need characters, and creating them comes before the adventure starts. If the game is as new to them as it is to you, take that whole night to help them create their characters. It's fun all on its own, and it allow's everyone to be familiar with the other characters -- something vital to party survival.

I'm not going to go into detail about the process of rolling up characters, because, like you, Klaatu and I have dedicated an evening just to this process. In a previous episode in this mini-series, the two of us created a character from the ground up, so you can hear what's involved, and how you might want to approach the process with your own players.

Klaatu

If designing your own custom dungeon seems intimidating to you, there is another way. And it's a time-honoured, legitimate way to play, and it's quite often the way I play: you go find an adventure that someone else has already written.

An adventure is the scenario you and your players experience when you sit down at the table to play. It's arguably the *game* (the rulebooks are the game engine, or the mechanics). Wizards of the Coast, Paizo, Catalyst, Kobold Press, Frog God, and many others publish adventures (sometimes called "modules", "scenarios", or "adventure paths") written by professional game designers. Published adventures provide the story framework for your game.

Not all systems publish adventures, though, or you may choose not to use one. If that's the case, spend some time developing a story. Writing a good game is part science, part craft, and part magic, but if you and your players are up to the challenge, then running blindly through a story that's mostly being created spontaneously on the spot can be a lot of fun. If that sounds overwhelming, though, get a published adventure!

Quick tip: Free, small, or introductory adventures are often available from https://drivethrurpg.com, https://dmsguild.com, and https://www.opengamingstore.com

Many adventures have text blocks that provide you with introductory text for each part of the game, they explain clearly what the goal of the players is during that segment, and give you guidance on what players will find in the area and how those discoveries lead to the next plot point.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of published adventures: there are "one-shots" and there are "modules" or "adventure paths".

A one-shot adventure is analogous to a quest in a video game: it's a single, clearly-defined task with a very obvious and immediate result; for example, goblins are terrorizing the hapless citizens of the local village, so go to their cave and clear it out: if you do, you'll relieve the villagers of the horrors, and you get to keep any gold or weapons you find.

The advantage is that it's designed to be a quick, one-time game session, so it's perfect for playing with friends you only see once in a while, or with someone who's never played before and just isn't sure if it's something they want to commit to. Don't be fooled by the page count of these small adventures: it may only be 5 to 10 pages long, sometimes less, but you'll be surprised at how long players can spend exploring a boundless world existing only in their imagination.

Adventure paths or modules or campaigns are bigger stories with loftier goals. You can think of them as lots of little one-shots strung together so that once players accomplish all the tasks and solve all the mysteries over the course of 200 pages, they have a final showdown with some Big Bad, and win themselves a place in the legends of the game world. It's an epic poem instead of a short story. It feels grander, it feels important. The losses along the way are more profound, and the victories sweeter. These campaigns take months to play through and usually expect a gaming group to meet weekly or fortnightly or at least monthtly to work their way through the tale.

I should mention one more kind of book you might stumble across, and those are source books. I mention this because I've had friends go and buy books more or less blindly, and then they bring them back home disappointed that instead of a book of lore about dark elves, they bought an adventure set in the underdark. Or the other way round: they wanted an adventure and ended up with a rule book.

This happens with the bigger systems that produce a lot of media, like {D&D, Shadowrun, Pathfinder, Warhammer}, so get clarity on what you're buying before you make a purchase. If you come across a cool ShadowRun book called RUN FASTER expecting a campaign to run with your friends, you'll be surprised to find that you've purchased a source book full of metatypes, expanded rules, and alternate character creation methods: sort of a Shadowrun Core Rulebook part 2. Same goes for, say, Volo's Guide with D&D, or Ultimate Campaign in Pathfinder. It can be overwhelming and they're not aways labelled clearly (or if they are, the label gets lost in the word cloud of RPG jargon that you're not used to yet), so do a little research first.

I've played through dungeons that a GM created over his lunch break, and I've played through adventures written by clever game designers, and I can confidently say that they're both great ways to RPG. But as a GM, if you feel overwhelmed by the idea of designing a dungeon, a published adventure is a great way to start. Aside from reading a chapter ahead before each game night, all the prep work is done for you, and there's very little thinking required.

Another part of being GM is deciding when a die roll is necessary. Die rolls represent the chance of success or failure when a specific action is taken, but the confusing thing is: if you think hard enough about anything in the world you can find a chance of success or failure. As a GM, it's up to you to decide what's "important" enough for a roll. Strictly speaking, that's determined by the rules. The rules told you what requires a roll, and you're expected to know the rules well enough to make the call.

In practise, however, you have a lot of stuff to track in you head, and remembering what requires a die roll, or deciding to request a die roll even though it may not be strictly required, can feel overwhelming for a new GM.

Good news: Players intuitively know when to roll dice. A player knows their character's skills (because they built the character and wrote it down on their character sheet), so sometimes the actions they choose to take are chosen because it falls within a category of a skill they happen to have. A thief probably wouldn't ever think to *look* for hidden door if the thief were a fighter (who would more likely think to pound on the wall rather than to slyly look for a hidden door). So if your player reaches for dice, let them roll because they're probably right.

I'm sure it's possible to take it too far, but people like to roll dice. It's part of the fun of an RPG, the uncertainty of subjecting yourself to the whims of fate. So when in doubt, either make your players roll dice, or roll dice yourself. I use dice rolls to help me decide everything from NPC reactions to weather conditions. It's usually safe to default to rolling.

Worst case scenario is that die are only picked up for fights and a literal interpretation of skills: and that works because those are the rules as written.

Klaatu

Players drive the story. In video game or movie terminology, they control the "camera". When players are exploring or investigating, let them ask questions or take actions ("I look in the closet"), and answer them as you see fit ("You open the closest and see an array of fine garments.")

"I'll move the clothes aside and examine the walls, and the floor. I'm looking for trap doors or hidden compartments, or anything suspicious."

And so on. Players can choose to investigate and explore for as much as they want. That's the beauty of a pen-and-paper RPG: the world is infinite. That said, you're the GM and you owe it to your players to keep the game moving. You don't to let your players spend 3 real hours searching a room that, in the end, has no bearing upon the plot whatsoever. That can be a delicate matter, because the nature of the game means that you know things that the other players don't, meaning much of the puzzle for players is what they don't know.

Usually I let players explore a space on their own until I feel that they've explored the obvious parts of it, and then I remind them where the exits are, or I remind them how many other rooms there are to explore, or some subtle clue to say, without saying, that they've secured an area.

If players are especially suspicious of something, though, you certainly have the power to generate a subplot, and often times you should do that. It's fun for you and rewarding to players. For instance, if a player is convinced that there's a secret panel in a closet and spends a lot of time investigating, then you might decide that there IS a secret panel in the closet, and then roll on a random table to determine what could possible inside that compartment. Or you could leave the compartment empty, thereby creating a story hook to return to later...what used to be in that compartment? who took it, and why? What were the implications?

Keeping the gaming moving is an inexact, unscientific process, but usually it comes pretty naturally. When you start to get bored of the players exploring, you can bet that they're probably getting bored too, and that's when you know to urge them forward. If all else fails, you can always have something lure them from one space to another: a mysterious sound, an oncoming threat, or a supernatural or divine instinct.